We had a positive, if quiet, end to 2023. For the year we were up just under 16% (including dividends) compared to the UK market, up just over 6%. Our largest monthly draw down was less than half of one percent compared to the market which saw four notable draw downs in 2023. Two of these draw downs were over 8%. We are pleased to be able to look back on 2023 as a year in which we produced notably better than overall market performance, a performance that was positive, and a performance that was achieved with very low volatility.

The UK market benefitted in December by the ‘year-end rally.’ We did participate somewhat in this move but towards the middle of the month we decided that equities were getting both over extended and over enthusiastic. We are consequently starting 2024 in a fully hedged1 position. While there was certainly some logic to the move up in equity markets in December, we cannot help but think that equity investors are now betting on the arrival of a positive but extremely rare event. In addition, the arrival of this ‘soft landing’ along with interest rate cuts is at least somewhat discounted into markets.

Investors now seem to expect that the economies of the West are going to avoid recession, and at the same time as this, that there are going to be substantial interest rate cuts. With inflation falling and with most economies ticking along it is easy to see how this view has pushed up markets into the year end. A common feature of market psychology is for investors to forecast what they want and need to see. Sometimes investors do get what they want, but from our perspective, such a perfect, market positive outcome, is not especially likely.

From our perspective there are a few issues. The first is that looking back over fifty years, the US Federal Reserve or the Bank of England have never cut interest rates when unemployment is as low as it is today. The current unemployment data in the US (from November of last year) is an astounding low unemployment rate of only 3.7%. In the UK unemployment is not much higher. Under any economist’s definition this would have to count as being full employment. Looking back at economic data during the past fifty years it has been the case in the UK and in the US that inflation tends to pick up when unemployment rates are at 5% or below. With the current rate being around 4% this would suggest that the amount of disinflation we can expect from here is limited. In addition, unless there is a sharp pick up in unemployment the consequences of cutting rates would imply a rapid return in inflation. This tends to make us feel that if the bulls on the economy are correct, and that a recession can be avoided, then there is very little scope for interest rates to fall. Alternatively, if interest rates do decline notably, it will probably be because a recession has arrived, and that unemployment has risen. It seems unlikely that the market can have its cake and eat it.

In relatively recent history we can find only one example of when interest rates were cut without there being an economic downturn or negative event of some sort (and along with this a substantial equity market pull back). This was in the years 1995 to 1996. The deep early 90s recession, along with the disinflationary forces of both China entering the world economy as a powerful exporter, and the rise of the tech industry all helped to push down inflation. UK interest rates peaked at 6.6% in February 1995 and were then cut to 5.7% by June 1996. To put this into context, base rates today are at 5.25% – a level which is already lower than the trough seen in 1996. It is also the case that in the mid-1990s the UK unemployment rate was around 8% – a level that is essentially double where it is now. Furthermore, after around a 1% cut in base rates in the mid-90s, UK rates then began to climb again, reaching 7.25% before the Asian and then the Russian crisis of 1998 arrived.

It is also the case that the financial position of the US was in a much healthier state. US government debt to GDP was around 65%. Today debt to GDP is over 130%. In addition, looking at US equities from a cyclically adjusted valuation perspective they are roughly 50% more expensive now than they were in the mid-90s.

A key final difference was the shape of the yield curve both in the UK and the US. In the mid-1990s the yield curve stayed positively sloped implying that there was not going to be a recession – and indeed there was not. Today we have a sharply negative yield curve which has successfully predicted the arrival of a recession every occasion it has occurred (five times) since the 1970s. Our expectation is that a recession is still more likely than not – and if this occurs then interest rate cuts are likely – but that equities would likely perform poorly as earnings estimates fall. Given the risks ahead we will proceed cautiously and quite apart from the economic and market risks ahead there is a lot of political volatility to navigate in 2024. A controversial and tense Presidential election will take place in the US. The UK may also have a general election and the troubled situation in the Middle East and the Ukraine are not yet over.

We would like to wish all the readers of this letter, and our investors a happy and prosperous year ahead. We will do our best to defend capital when appropriate and deploying it to make money when it makes sense to do so.

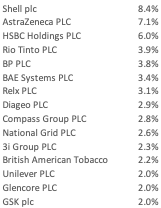

TOP FIFTEEN EQUITY HOLDINGS 29th DECEMBER 2023